Mental health is quite the subject these days, its troubles affect everyone; it knows no gender, orientation, race — it strikes upon one’s inner journey. But specifically, what have not been put in the same sentence are men, mental health and vulnerability. Too often it is seen that men are not allowed to show their emotions. But the aftermath shows that this repression of emotions bleeds into relationships, substance abuse, domestic violence, and more. It is seen time and time again in films, books, art — it’s all too familiar.

And it is beyond the point of “let’s talk about it.”

Time for action.

Mental health hits close to home for me. As a filmmaker, I will always share my journey with others.

– Jacquile Singh Kambo

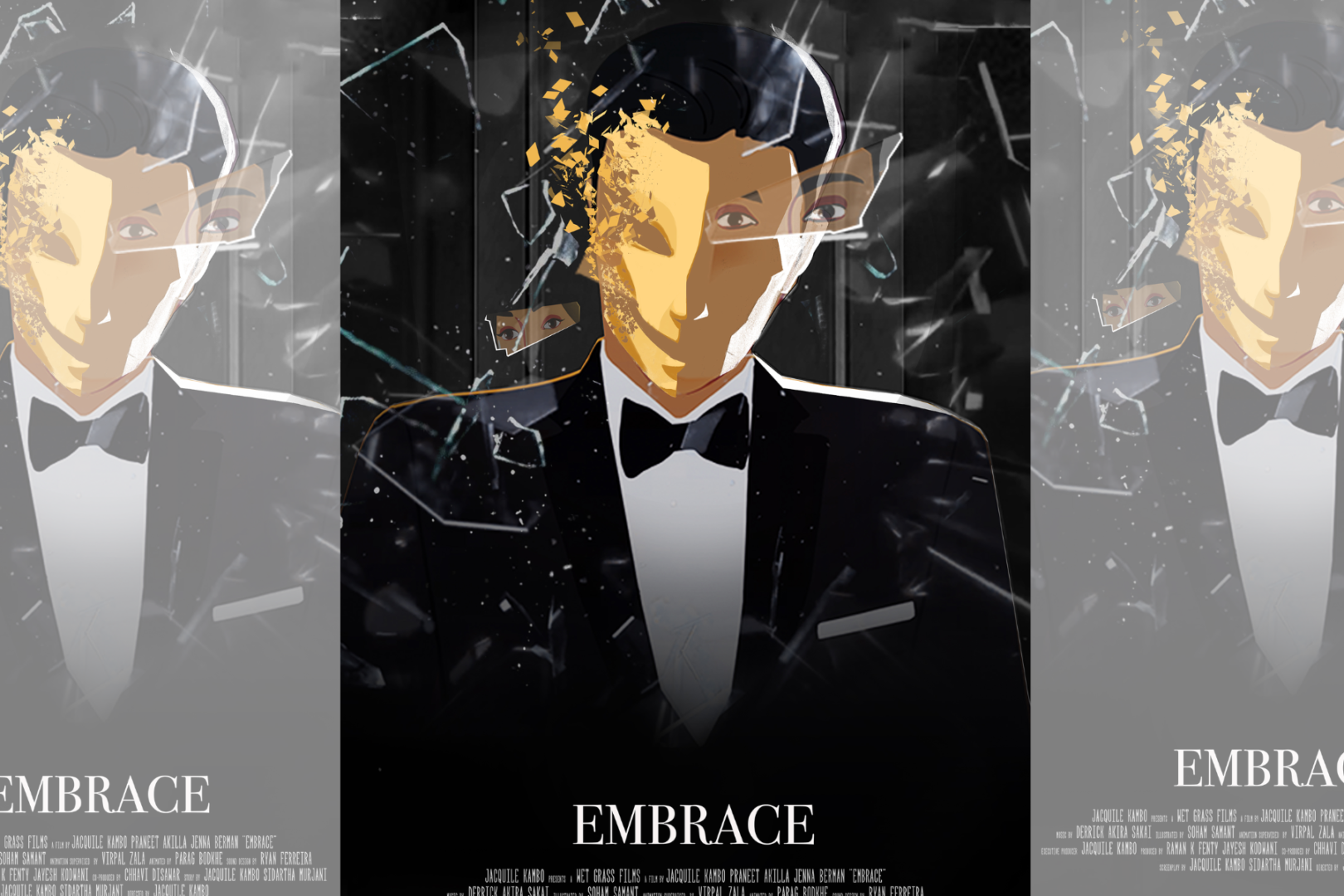

Men, mental health and vulnerability often aren’t talked about enough. “Embrace” is a short film that seeks to change that. It is a short animated film about Arty, a well-dressed man who has no face, gets ready for his date until he meets a younger version of himself. Arty and this younger version of himself delve into a surreal world where he learns to embrace himself. It’s him versus himself.

Not often is it discussed that men should have a safe environment to be vulnerable, amongst others or even other men. Perhaps this is because men are wired to put on a façade when things go wrong, when things get difficult, or when true emotions are not expressed. If these are not dealt with, it can lead to other relationships, including romantic relationships. Further it becomes a cycle: suppression could lead to aggression, substance abuse or self-sabotaging behaviors and could create a toxic environment. Many of these arise from childhood trauma. Quite often childhood is repressed or ignored, and one may take their troubles along with them into adulthood. Perhaps revisiting the roots of the past can help one become successful in a better tomorrow. “Embrace” is an example of how important it is for men to embrace their past.

[Read related: Schism: A Journey to Finding My Own Identity]

Why Animation?

“Embrace” was meant to be a live-action film — until animation was considered. Seven years of re-writing, re-working, and digging down deep with the characters for the story to better fit the message at its core. Animation is an underrated avenue for a universal story that became the key pillar for “Embrace”. What many do not know about animation is that you can create a serious subject matter in a light-hearted way that is universally acceptable. Men and mental health are heavy subjects for some, but animation allows the exploration to become innovative, creative and fun. Animation allows the experimentation of entering surreal worlds.

For example, in “Embrace” Arty enters a surreal world where he has to go up against a younger version of himself — to unmask the root cause of his internal struggles and give himself the “big hug” he needs. This heart-throbbing metaphor is captured in animation that a live-action film couldn’t have captured. The freedom of animation helps tackle tough subject matters about self-love, and how we must embrace the soul, the child, the person within.

The Story Behind The Story

There are many inspirations behind “Embrace”. Film noir, the silent film era, surrealism and the works of Christopher Nolan and David Lynch — the film is able to articulate something far more special. This is more than just a mental health piece for educational purposes. This is a classical narrative from beginning to end; a story of important themes and beloved characters that needed to be shared with the world.

It is not often the words mental health and men and vulnerability are discussed under the same umbrella — especially with growing hypermasculinity, and the likes of social media where facades are put up and the vulnerable parts of ourselves aren’t as expressed. It is here where the film encourages men to look within themselves, and allows them to be vulnerable to themselves. Perhaps this is an important step to better themselves on the journey to have successes (whatever success means to them), and to enlighten and lift those around them. The first step should always begin with “you.”

[Read related: Truth Be Told: Breaking the Silence on a Silent Killer, Mental Illness ]

A Call To Action

It’s tough to find places where men have access in ways of improving their mental health without feeling like a patient or a victim in the institutionalized realm. It’s tough to find places where men can talk to other men about their struggles among peer groups, educational groups, and more.

The “Let’s Talk” phase and awareness is long overdue; it is indeed time for action. Perhaps creating seminars or group-related events and activities to help create vulnerable environments. Art or art therapy can be a great way of producing something stemming from the inner journey. Or maybe it is time to look at “sick days” as “mental health days” as well. Perhaps more can be done to simply just talk about it. It’s time to give ‘doing’ a chance to start in our close-knit communities.

Maybe if one learns to ’embrace’ themselves, only then, perhaps one can fully understand others and their pain — and have the vision of empathy for others. “Embrace” took seven years to write and a year of animation for a four-and-a-half-minute short film. The film is about self-love, embracing one’s self before one can see empathy for others. It is produced by Raman K Fenty and Jayesh Kodwani and his team, directed and written by Jacquile Singh Kambo, co- written by Sidartha Murjani and stars Jenna Berman. “Embrace” has received numerous international accolades including Best Audience choice at the Emerging Lens Cultural Film Festival of Halifax, Nova Scotia, as well as acceptances in hometown Vancouver, Canada; Goa, India and Chicago, United States.

If you are struggling with your mental health, please call your regional crisis hotline. These are a few non-crisis mental health resources for men’s mental health.

- https://headsupguys.org/

- https://movingforward.help/

- https://www.sochmentalhealth.com/

- http://samhaa.org/

Feature Image Courtesy: Jacquile Singh Kambo as Embrace promo