by Mayura Iyer – Follow @tweetsbymayura

“So, your students must be horrible, right?”

I’ve gotten this comment in multiple forms from various people, but especially from people within the South Asian community. I’m a high school teacher in Texas, at a Title I school where the population is 93 percent Hispanic/Latinx and 88 percent low socioeconomic status. In contrast, I went to a high school in Northern Virginia, which was one of the top 100 high schools in the nation, and in one of the most affluent counties in the country. I was surrounded by high-achieving students, South Asian or otherwise, and never had to think twice about access to a good public school. So when I would explain to people I grew up with — especially my South Asian peers — that the school I taught at was different than the schools we had attended, I was often met with thinly masked racist comments.

“Your job must be so hard — I bet they never listen to you.”

“What do you mean they haven’t learned English yet? Are they even trying?”

“Do they even value an education?”

Many of the comments that I’ve gotten have fallen into this trap — the trap of blaming my largely Mexican-immigrant students for their socioeconomic status due to their perceived lack of hard work or apathy towards education. I’ve seen this attitude throughout the South Asian community, and the broader Asian American community as well. So many of us have fallen into this trap, believing that because we somehow made it in America that all other minorities must be able to make it too, if they just worked hard enough. This is because too many of us have come to believe that as Asian immigrants, we are superior to other immigrants, or other racial minorities. We’ve fallen into the trap of the “model minority.”

The Model Minority Myth

“Asian American”, or Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) is often used as a vague descriptor for one of the most diverse racial groups in the world — a word used to describe people across multiple ethnicities, cultures, and languages, from Pakistani-Americans to Polynesian-Americans. And all too often, this vague and diverse racial group is reduced to the stereotype of the “model minority” — the idea that AAPIs have immigrated to this country and achieved the ever-elusive American Dream by working hard, and have the amassed the education and wealth to prove it. In a column for the New York Times, Nicholas Kristoff cites the “Asian Advantage”, saying that members of the AAPI community are more highly educated than the average American (yes, including those who are white). Other statistics show that members of the AAPI community have median household incomes comparable to their white peers. However, these statistics are incomplete and misleading and only serve to bolster the myth of the model minority.

There are two issues with this “model minority” myth:

1. It buoys a racist system that hurts “non-model” people of color in this country.

2. The stereotype of the “model minority”, like all stereotypes, is an incomplete narrative of the stories and struggles of the AAPI community.

To label one minority, and one group of color as the “model” is to imply that all other groups of color are “non-model”. It implicitly casts blame on other racial minorities in the U.S. for their socioeconomic obstacles. It says to African-Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans “Hey, if Asians can come to this country and ‘make it’, why can’t you?” It says to these groups “We see your struggles, but clearly you’re not trying hard enough.” It says to these groups “Why can’t you be more like them?” It invalidates the struggles of other groups of color and equates the oppression and racism felt by those groups with those of the AAPI community. This is not to say that the AAPI community doesn’t face oppression — however, the oppression of one group of color is not the same, nor equal, to the oppression of other groups of color.

Education and the Model Minority

[Full-size versions of these graphs available through the Center for American Progress ]

[Full-size versions of these graphs available through the Center for American Progress ]

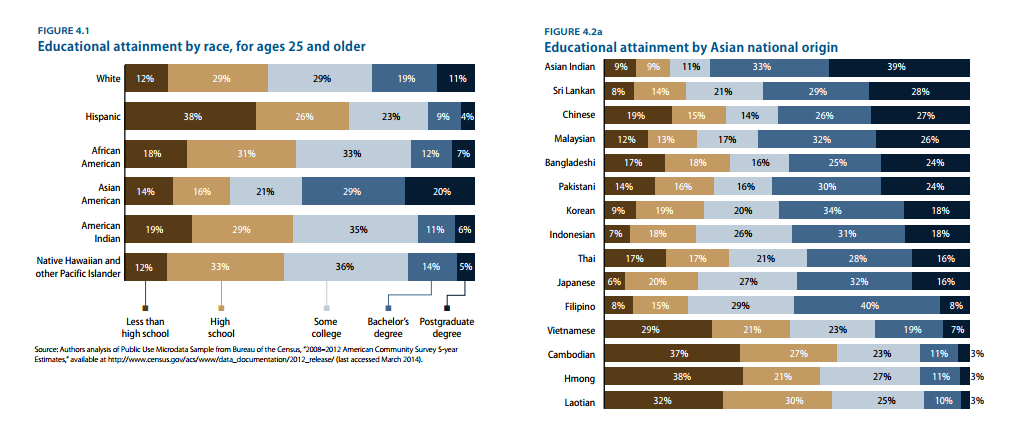

Additionally, to label all persons within an enormously diverse and heterogeneous racial group as the “model” inevitably masks large pockets of poverty, struggle, and oppression. Yes, when you look at the AAPI community as one pervasive umbrella, it can be easy to assume that all Asian-Americans are economically successful and highly educated. However, this largely only applies to Indian-Americans and Chinese-Americans, many of whom came to the U.S. through a visa program that favors highly educated Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) professionals. In particular, according to an analysis of census data done by the Center for American Progress, Bangladeshi, Hmong, Cambodian, Thai, and Vietnamese Americans have some of the lowest rates of college and higher degree attainment in the U.S. A study by the Brookings Institute shows that there are also vast differences in access to good schools within the AAPI community, with Hmong and Bangladeshi Americans having much lower access to good schools than Indian and Chinese Americans.

[Full size version of this graph available at the Brookings Institute]

[Full size version of this graph available at the Brookings Institute]

Because of the pervasiveness of the model minority myth, studies such as the ones by the Center for American Progress and the Brookings Institute are few and far between. There is little research on the AAPI community in general, much less the subgroups that fall under that umbrella. This means that Congress, policy groups, and school systems are unable to recognize and respond to the diverse circumstances of AAPI students. Instead, members of the AAPI community are lumped under an incomplete stereotype, and their needs are neglected.

In our school system, this also means teachers may carry implicit biases towards AAPI students and view them as inherently smarter than other minority students. This can lead to preferential treatment towards AAPI students and even greater harm to other racial minorities in the classroom as teachers begin to believe that there is such as thing as “model” and “non-model” minority. Additionally, this often leads to teachers and schools ignoring the needs of AAPI students by assuming that they don’t have any educational needs. In particular, AAPI students who are English Language Learners (ELL) are left at the margins. As a report by the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund (AALDEF) notes, most schools don’t provide services to ELL students, especially when those students’ first language is a language other than Spanish. Nearly 1 in 4 AAPI students are ELL. Between the ages 5 and 17, 52 percent of Hmong Americans, 39 percent of Vietnamese Americans, 34 percent of Bangladeshi Americans, and 33 percent of Cambodian Americans are ELL.

Because of these statistics, advocates in the AAPI community are pushing for data disaggregation — a push to split data by ethnic groups within the AAPI community so that information can be gathered to meet the needs of at-risk groups, including Hmong, Cambodian, Bangladeshi, and Vietnamese Americans. However, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), the most recent iteration of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the most comprehensive piece of legislation in U.S. education policy, did not include any measures to disaggregate data for the AAPI community. The power and pervasiveness of the model minority myth has allowed our education system to ignore the issues facing marginalized groups within the AAPI umbrella.

However, the power and pervasiveness of the “model minority” myth does not just come from the dominant white culture — it comes from members of our own AAPI community buying into the myth. Many members of the AAPI community — including South Asians — look down on other racial minorities for their seeming inability to break the cycle of poverty the way immigrants in our community seem to have done so. I’ve seen this through anti-blackness within the AAPI community. I’ve seen it in the faces of my family members once they learn that many of my students are undocumented (despite the fact that Indians are the fastest growing group of undocumented immigrants). We continue to put down other immigrant groups and hold ourselves up to the pedestal as the “model” for others to follow. We puff our chests and inflate our egos believing that we are the true proof of the American Dream, that we do better because we value an education more and work harder than any other minority in this country. The model minority myth persists not just because white people believe it — it persists because we believe it.

A Call To Action

While the model minority myth has persisted for decades, the AAPI community is beginning to speak out. However, there are several additional steps that we, as a South Asian community, can take to push back against this stereotype.

1. Support politicians and campaigns that support data disaggregation for AAPI students.

Look up your representatives, and see whether or not they have ever released a statement regarding data disaggregation or services for AAPI students. Find out what your representative has done for the AAPI and South Asian community. Donate to and support organizations that are campaigning against the model minority myth. Some non-profits, like OCA – Asian Pacific American Advocates, actively advocated for data disaggregation during the time of the passage of the ESSA. Do your research, and see how you can get involved.

2. Celebrate and elevate diverse narratives in the South Asian and AAPI community (and call out the narratives that are one-dimensional).

Over the past few years, we’ve started to see greater representations of AAPIs and South Asians in television — and more nuanced representations of these groups. From Crazy Ex-Girlfriend to the Mindy Project, AAPIs are taking over television, and in ways that go beyond the typical tropes assigned to us. Even collections of poetry such as “Milk and Honey“ by Rupi Kaur and the novels of Jhumpa Lahiri have brought to light aspects of the South Asian immigrant experience that would have not otherwise been seen. We need to elevate the stories of South Asians and AAPIs who break the mold and celebrate when people show nuanced AAPI characters in literature and television.

However, even with increasing diversity in literature and television, we cannot allow one-dimensional representations of our community to persist. One way to break one-dimensional representations is by joining in on campaigns against stereotypes surrounding AAPIs and South Asians. Some college campus organizations have launched campaigns to tackle the model minority myth, and Brown Girl Magazine recently worked alongside the Washington Leadership Program to launch our own campaign to fight against stereotypes in the South Asian community.

3. Be an ally within the AAPI community and across other communities of color.

Part of the reason the model minority persists is because of the racist systems that use it as a weapon against other communities of color. By allying with other racial minorities, and by confronting the anti-blackness within our own community, we can work against the model minority myth and prove that there isn’t just one minority that is a “model” for others. Go to meetings for the Black Student Alliance or Latino Student Alliance at your college campus. Start conversations with your friends and family about the anti-blackness and racism you see around you. Challenge the notion that your socioeconomic status is only determined by “hard work.” Check your privilege, and encourage others to do the same. Show up for the causes that matter to other communities of color. Our struggles may be different, but they are not separate.

With fears of a weakened public school system and anti-immigrant rhetoric on the rise, it is crucial that we work to remedy the harmful consequences of the model minority myth, both on the AAPI community and on other racial minorities — particularly within our school systems. Not all AAPIs are highly educated; not all AAPIs have access to good schools; not all AAPIs have access to the services they need within their schools, and it harms both ourselves and other marginalized groups to buy into the racist myth that we are superior to other minorities. Without a complete and multi-dimensional narrative of AAPIs within the school system, it will be impossible for AAPIs to have equal educational opportunity, and thus impossible to have equal economic opportunity. Most importantly, as long as we continue to believe the model minority myth, as long as we remain in the trap of putting down other minorities and holding ourselves up as a paragon of the American Dream, the model minority myth will continue to exist. Breaking the model minority myth doesn’t just benefit the AAPI or South Asian community — it benefits everyone.

Mayura Iyer is a graduate of the University of Virginia and is presently pursuing a Master of Public Policy. She hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in Literally, Darling, BlogHer, and Mic.com.

Mayura Iyer is a graduate of the University of Virginia and is presently pursuing a Master of Public Policy. She hopes to use her policy knowledge and love of writing to change the world. She is particularly interested in the dynamics of race in the Asian-American community, domestic violence, mental wellness, and education policy. Her caffeine-fueled pieces have also appeared in Literally, Darling, BlogHer, and Mic.com.